The Public Book Club, AB (Almenna bokafelagid), has a long prehistory. Under the leadership of a staunch Stalinist literary critic, Kristinn E. Andresson, and with substantial help from Moscow, communists became dominant in Icelandic culture in the 1930s and 1940s. They operated a left-wing book club, Mal og menning (Language and Culture), and ran a publishing house, Heimskringla. They not only published a daily, but also two quarterly magazines, the literary review Timarit Mals og menningar and the more political Rettur, both uncompromisingly supporting revolutionary writers such as Halldor Laxness, Thorbergur Thordarson, Johannes from Katlar and Halldor Stefansson, at the same time as more moderate authors like David Stefansson from Fagriskogur, Tomas Gudmundsson and Gudmundur G. Hagalin were mocked and even ridiculed in the communist press. For a while, an Association of Revolutionary Writers operated, to become redundant in 1944 when communists gained control of the Icelandic Writers’ Association (Rithofundafelag Islands); their coup however resulted in some moderate writers, at the initiative of Gudmundur G. Hagalin, walking out and forming the Association of Icelandic Writers (Felag islenskra rithofunda).

Meanwhile, democratic anti-communists tried to inform the general public about communism, not least about the Soviet regime. In the autumn of 1938, for example, the Icelandic Christian Students Association published an Icelandic translation of a book which had then recently appeared in Finnish and Swedish, Thjonusta, thraelkun, flotti (Service, Serfdom, Escape). The author, Aatami Kuortti, was a Finnish pastor who had served in Soviet Ingermanland, been sent to a labour camp and managed to escape to Finland. This book appeared at the same time as a travelogue from Iceland’s best-known author, Halldor Laxness, Gerska aefintyrid (A Russian Adventure), where life under Stalin was described in glowing terms. The publishing company Isafoldarprentsmidja published in 1942 and 1944 two works by the Russian dissident Ivan Solonevich, I fjotrum (Russia in Chains) and Flottinn (Escape from Russian Chains). When the publishing house of the trade unions, MFA, decided in 1941 to publish the first volume of Jan Valtin’s Out of the Night (Ur alogum in Icelandic), the communists mounted a campaign against it, with the result that the second volume was published in 1944 not by the MFA, but by ‘A Handful of Fellows’ who remained anonymous. In his lively book, Jan Valtin, or Richard Krebs, described his life in the 1920s and 1930s as an agent of Comintern, the International union of communist parties.

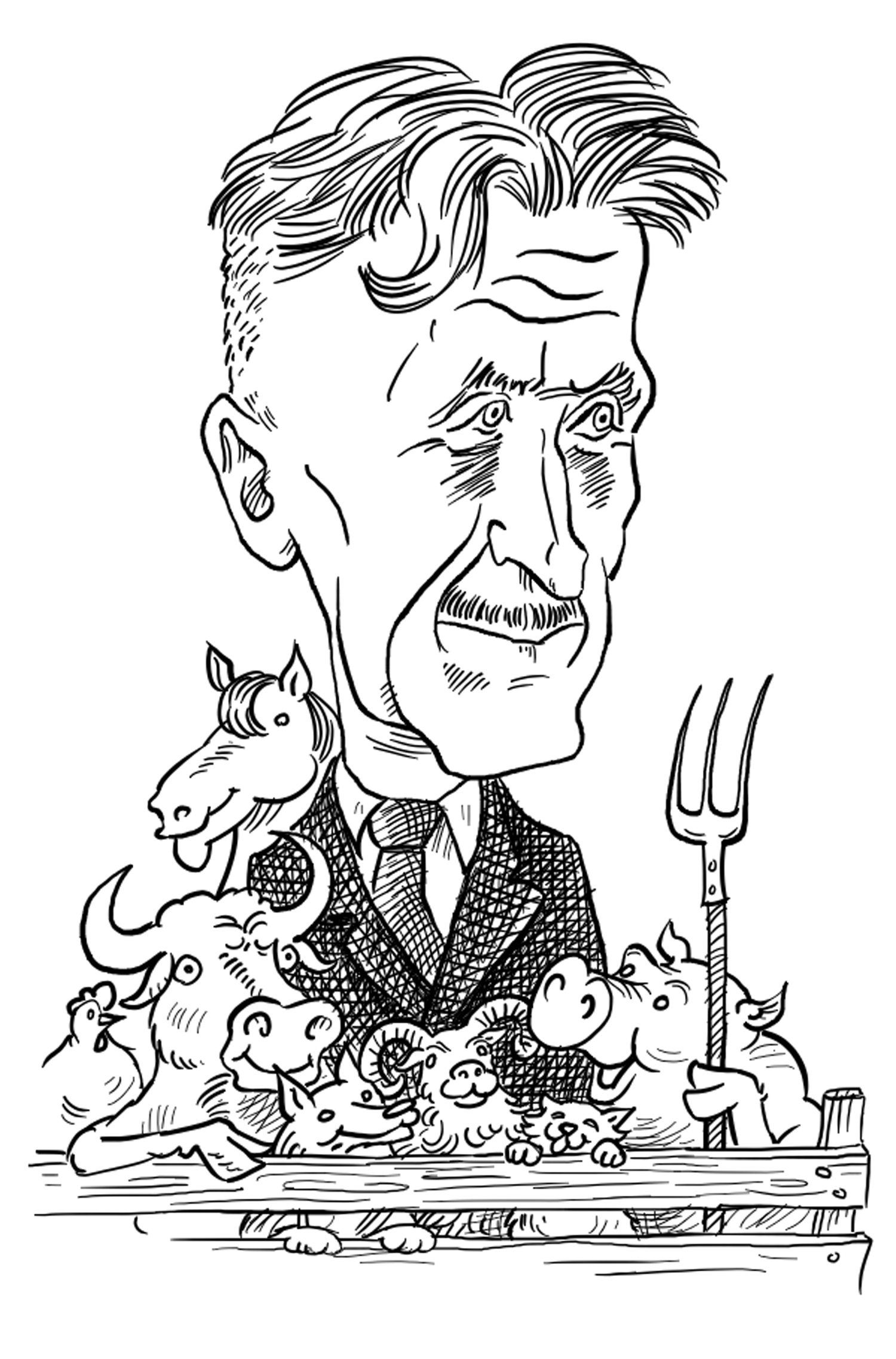

Individual efforts continued to be made to provide information about life in the Soviet Union, however loudly the well-funded communist propaganda machine ground. The lawyer Larus Johannesson, member of parliament for the Independence Party, translated and published himself in 1951 the famous I chose Freedom (Eg kaus frelsid in Icelandic) by Victor Kravchenko, a Russian refugee. The communist daily immediately alleged that Larus was funded by the CIA. Two years earlier, Larus had published Animal Farm (Felagi Napoleon in the Icelandic translation) by George Orwell, the fable based on the Russian Revolution. Snaefellsutgafan, a small publishing company, in 1947 brought out Darkness at Noon (Myrkur um midjan dag in Icelandic) by Arthur Koestler. More than a well-told novel, it is an attempt to explain psychologically the strange confessions of Stalin’s victims in the Moscow trials. Koestler’s message had been hotly debated in 1946 when Morgunbladid printed chapters of his The Yogi and the Commissar in a special issue.

Two young idealists, Geir Hallgrimsson and Eyjolfur Konrad Jonsson, started publishing books about communism in 1950 with The God that Failed (Gudinn sem brast in Icelandic), by Koestler, André Gide and other former communists or “fellow-travellers”. Their second book was Nineteen Eighty Four in 1951, Orwell’s dystopia about totalitarian society. In 1952, their publishing company, called Studlaberg, brought out El Campesino by Valentin Gonzalez who had fought in the Spanish Civil War and later fled to the Soviet Union. Geir Hallgrimsson and Eyjolfur Konrad Jonsson had a meeting with Iceland’s best-known anti-communist, Bjarni Benediktsson, former law professor and now Minister of Culture and Vice-Chairman of the Independence Party, where they discussed the need to counter the communist dominance of cultural life. Bjarni Benediktsson agreed that they should form a book-club, similar to the communist-controlled book-club Mal og menning, and on 17 June 1955 the Public Book Club (Almenna bokafelagid or AB), was founded. Many of Iceland’s prominent writers joined AB, including Gunnar Gunnarsson, Tomas Gudmundsson, David Stefansson from Fagriskogur, Gudmundur G. Hagalin, Kristmann Gudmundsson and Kristjan Albertsson. Bjarni Benediktsson was the first chairman of the AB board, and Gunnar Gunnarsson the first chairman of its literary council. Eyjolfur Konrad Jonsson was the company’s first director.

One of the first books that AB published was Baltic Eclipse (Orlaganott yfir Eystrasaltslondum in the Icelandic translation) by Professor Ants Oras, describing the Soviet occupation of the three Baltic republics. Soon after the Hungarian uprising of 1956, AB brought out an account of it, Thjodbyltingin i Ungverjalandi (The Hungarian Nation Rises Up), by Danish journalist Erik Rostboll. AB published many other books which would never have passed the editors of Soviet-funded Mal og menning, such as The New Class by Milovan Djilas, Doctor Zhivago by Boris Pasternak, and One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. AB also published collected works of many Icelandic anti-communist writers, Gunnar Gunnarsson, Gudmundur G. Hagalin, Tomas Gudmundsson, Kristmann Gudmundsson and others. Mostly, however, the AB books were of general interest, and gradually it became less political. Nevertheless, it published in 1973 an account of Soviet oppression in Estonia, Eistland undir oki erlends valds (Estonia under Foreign Tutelage) by Estonian-Swedish writer Anders Küng, translated by David Oddsson, then a law student, later to become Prime Minister of Iceland and instrumental in reaffirming Iceland’s recognition of the three Baltic States in 1991.

The AB literary council, 1970. From left: Tomas Gudmundsson (chairman), Kristjan Albertsson, Dr. Sturla Fridriksson, Matthias Johannessen, Dr. Johannes Nordal, Indridi G. Thorsteinsson, Birgir Kjaran, Hoskuldur Olafsson og Guðmundur G. Hagalin. Standing, Baldvin Tryggvason and Pall Bragi Kristjonsson.

AB went through a difficult time in the early 1990s, and in 1996 it had to file for bankruptcy. Its ancient rival, Mal og menning, also had financial difficulties, but managed to resolve them by merging with other non-political or only mildly left-wing publishing companies.

In 2011, the AB name and trademark was bought and revived by the same group of people who were then behind RNH, the Icelandic Research Centre for Innovation and Entrepreneurship. Jonas Sigurgeirsson is managing director of the publishing house. The books published by AB since then include:

- Islenskir kommunistar 1918–1998 (Icelandic Communists 1918–1998) by Professor Hannes H. Gissurarson, 2011

- Uppsprettan (The Fountainhead) by Ayn Rand, translated by Thorsteinn Siglaugsson, 2011

- Icesave-samningarnir. Afleikur aldarinnar? (The Icesave Deals: The Blunder of the Century?) by journalist Sigurdur Mar Jonsson, 2011

- Undirstadan (Atlas Shrugged) by Ayn Rand, translated by Elin Gudmundsdottir, 2012

- Busahaldabyltingin: sjalfsprottin eda skipulogd? (The Pots-and-Pans Revolution: Spontaneous or Planned? by historian Stefan Gunnar Sveinsson, 2013

- Kira Argunova (We the Living) by Ayn Rand, translated by an unknown translator in 1949 and then serialised in Morgunbladid, 2013

- Tekjudreifing og skattar (Income Distribution and Taxes), ed. by Ragnar Arnason and Birgir Thor Runolfsson, and also with contributions from Hannes H. Gissurarson, Helgi Tomasson, Axel Hall and Arnaldur Solvi Kristjansson, 2014 (also online)

- Heimur batnandi fer (The Rational Optimist) by Matt Ridley, 2014

- Andersen-skjolin (The Andersen Files) by journalist Eggert Skulason, 2015

- Eftirlystur (Red Notice) by US investor Bill Browder, 2015

- Barnid sem vard ad hardstjora (The Child That Turned into a Despot) by journalist Bogi Arason, 2015

- Gjaldeyriseftirlitid: Vald an eftirlits? (The Currency Supervision Authority: Authority Without Supervision?) by Bjorn Jon Bragason, 2016

- Med lifid ad vedi (In Order to Live) by North Korean refugee Yeonmi Park, 2017

- Framfarir (Progress) by Johan Norberg, 2017

- Tólf lifsreglur (Twelve Rules for Life) by Jordan Peterson, 2018

- Afnam haftanna: Samningur aldarinnar? (The Abolition of Economic Controls: The Deal of the Century?) by Sigurdur M. Jonsson 2020

- Ut fyrir rammann (Beyond Order) by Jordan Peterson, 2021

- Uppgjor bankamanns (A Banker’s Reckoning) by Larus Welding, 2022

- Landsdomsmalid (The Impeachment Case Against Geir H. Haarde) by Hannes H. Gissurarson, 2022

AB is going to publish more online editions of many of the books which came out during the struggle with totalitarianism and are now out of print. Those that came out in 2015–2019 were:

- Greinar um kommunisma (Articles on communism) by philosopher Bertrand Russell

- Konur i thraelakistum Stalins (Women in Stalin’s Slave Camps) by Elinor Lipper and Aino Kuusinen

- Ur alogum (Out of the Night) by Jan Valtin (Richard Krebs)

- Leyniraedan um Stalin (Khruschev’s Secret Speech on Stalin)

- El campesino by Valentín Gonzáles and Julián Gorkin

- Orlaganott yfir Eystrasaltslondum (Baltic Eclipse) by Ants Oras

- Eistland. Smathjod undir oki erlends valds (Estland. En studie i imperialism) by Andres Küng

- Thjonusta, Thraelkun, flotti (Service, Servitude, Escape) by Aatami Kuortti

- Eg kaus frelsid (I Chose Freedom) by Victor Kravchenko

- Nytsamur sakleysingi (Nightmare of the Innocents) by Otto Larsen

- Til varnar vestraenni menningu (In Defence of the West) by six Icelandic writers

- Radstjornarrikin: Godsagnir og veruleiki (Soviet Myths and Reality) by Arthur Koestler

- Framtid smathjodanna (The Future of Small Nations) by Arnulf Øverland

In 2024, AB will publish a two-volume history of the origins of the Icelandic communist movement by historian Snorri G. Bergsson. AB is also going to republish libertarian and free-market works, both online and on paper, such as Mystery of Capital by Hernando de Soto, Economics in One Lesson by Henry Hazlitt, The Law by Fréderic Bastiat and Vices Are Not Crimes by Lysander Spooner. Also forthcoming are translations of books by Niall Ferguson and Richard Pipes.