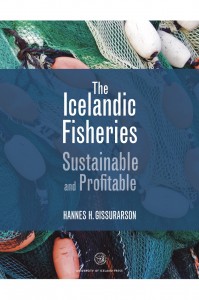

RNH is, in cooperation with Atlas Network and ACRE, the Alliance of Conservatives and Reformists in Europe, supporting the republication online by AB (The Public Book Club) of many books relevant to individual and economic freedom. In early 2016 a recent book by RNH Academic Director, Professor Hannes H. Gissurarson, was published, The Icelandic Fisheries: Sustainable and Profitable. In January 2017, a 2009 book by Professor Gissurarson was made available online, Ahrif skattahaekkana a hagvoxt og lifskjor (Impact of Tax Increases on Economic Growth and Living Standards). In the latter book Professor Gissurarson discusses the two most important philosophical cases for the welfare state, Hegel’s emphasis on social inclusion and Rawls’ concern for the worst-off. He argues that the “Icelandic model” pursued in Iceland under the leadership of David Oddsson in 1991–2004 met both Hegel’s and Rawls’ criteria. It provided for more social inclusion than most other societies because unemployment was insignificant, the poverty level was low, pension funds were strong and retirement age was relatively high. The worst-off in Iceland were better off than in most other countries and had the opportunity to better their conditions. In fact, during this period the income of the lowest-income group increased more rapidly in Iceland than in any other European country with the exception of oil-rich Norway. Professor Gissurarson presents evidence from the Fraser Institute’s Index of Economic Freedom that generally speaking the worst-off are best-off in free economies. Therefore, a Rawlsian social democrat ought to support the market economy, free trade and the rule of law. Professor Gissurarson also describes the success of comprehensive tax reductions in Iceland in 1991–2004, warning against tax increases.

RNH is, in cooperation with Atlas Network and ACRE, the Alliance of Conservatives and Reformists in Europe, supporting the republication online by AB (The Public Book Club) of many books relevant to individual and economic freedom. In early 2016 a recent book by RNH Academic Director, Professor Hannes H. Gissurarson, was published, The Icelandic Fisheries: Sustainable and Profitable. In January 2017, a 2009 book by Professor Gissurarson was made available online, Ahrif skattahaekkana a hagvoxt og lifskjor (Impact of Tax Increases on Economic Growth and Living Standards). In the latter book Professor Gissurarson discusses the two most important philosophical cases for the welfare state, Hegel’s emphasis on social inclusion and Rawls’ concern for the worst-off. He argues that the “Icelandic model” pursued in Iceland under the leadership of David Oddsson in 1991–2004 met both Hegel’s and Rawls’ criteria. It provided for more social inclusion than most other societies because unemployment was insignificant, the poverty level was low, pension funds were strong and retirement age was relatively high. The worst-off in Iceland were better off than in most other countries and had the opportunity to better their conditions. In fact, during this period the income of the lowest-income group increased more rapidly in Iceland than in any other European country with the exception of oil-rich Norway. Professor Gissurarson presents evidence from the Fraser Institute’s Index of Economic Freedom that generally speaking the worst-off are best-off in free economies. Therefore, a Rawlsian social democrat ought to support the market economy, free trade and the rule of law. Professor Gissurarson also describes the success of comprehensive tax reductions in Iceland in 1991–2004, warning against tax increases.

Tabula Gratulatoria – Ragnar Árnason

Coming Up

Research Areas

Roots

Blogs

Archives

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- May 2025

- March 2025

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- November 2023

- September 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- June 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- December 2020

- July 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- April 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- February 2012

- November 2011

- August 2009

-

Icelandic Research Centre on Innovation and Economic Growth

Fákafeni 11

108 Reykjavík

Sími 615 11 22RNH á YouTube

![ACRE[logo] copy[3][6]](http://www.rnh.is/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/ACRElogo-copy36-300x122.jpg)

![ACRE[logo] copy[3][6]](http://www.rnh.is/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/ACRElogo-copy36.jpg)