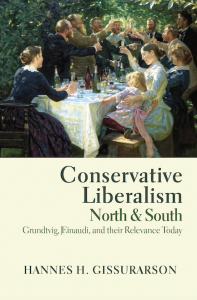

In 2024, the ECR Party, the European Conservatives and Reformists Party, published a study by Hannes H. Gissurarson, Professor Emeritus of Politics at the University of Iceland, Conservative Liberalism, North and South: Grundtvig, Einaudi and their Relevance Today. The book is in four chapters. The first chapter describes the origins of classical liberalism, in Icelandic chronicler Snorri Sturluson, and Italian philosopher St. Thomas Aquinas, and its articulation as a systematic theory by John Locke, David Hume, and Adam Smith. In the French Revolution, it split into the conservative liberalism of Edmund Burke, Benjamin Constant, and Alexis de Tocqueville, based on respect for spontaneously developed traditions and distrust of grand theory, and the social liberalism of Thomas Paine and John Stuart Mill, inspired by romantic individualism. In the second chapter, the Danish poet and pastor N.F.S. Grundtvig is presented as a spokesman for national liberalism. Grundtvig’s nationalism did not imply any desire to subdue or belittle other cultures: it was rather an exhortation to the Danish nation to protect and develop its national heritage, language, literature, history and folkways.

In 2024, the ECR Party, the European Conservatives and Reformists Party, published a study by Hannes H. Gissurarson, Professor Emeritus of Politics at the University of Iceland, Conservative Liberalism, North and South: Grundtvig, Einaudi and their Relevance Today. The book is in four chapters. The first chapter describes the origins of classical liberalism, in Icelandic chronicler Snorri Sturluson, and Italian philosopher St. Thomas Aquinas, and its articulation as a systematic theory by John Locke, David Hume, and Adam Smith. In the French Revolution, it split into the conservative liberalism of Edmund Burke, Benjamin Constant, and Alexis de Tocqueville, based on respect for spontaneously developed traditions and distrust of grand theory, and the social liberalism of Thomas Paine and John Stuart Mill, inspired by romantic individualism. In the second chapter, the Danish poet and pastor N.F.S. Grundtvig is presented as a spokesman for national liberalism. Grundtvig’s nationalism did not imply any desire to subdue or belittle other cultures: it was rather an exhortation to the Danish nation to protect and develop its national heritage, language, literature, history and folkways.

In the third chapter, the Italian economist Luigi Einaudi is presented as a spokesman for liberal federalism which looks with distrust on nationalism. Einaudi’s goals for Europe were peace, prosperity, and liberty. He believed that this could only be achieved by a European federation, not by a looser confederation, invoking the examples of the Kingdom of Poland, the American Confederation of 1781–1789 and the League of Nations. In the fourth chapter, the national liberalism of Grundtvig and the liberal federalism of Einaudi are compared. A contrast is drawn between the Nordic or Grundtvigian model of international relations—the right to secede, border changes by plebiscites, autonomy of nationalities, and cooperation aand coordination between states with a minimal surrender of sovereignty— and the European model, implemented in the European Union—ever-growing centralisation, a non-transparent and unaccountable bureaucracy and an activist and unaccountable judiciary.

The Icelandic Research Centre for Social and Economic Affairs, RSE, and the Institute of Studies in Administration and Politics at the University of Iceland jointly held an international conference in Reykjavik on Professor Gissurarson’s book on 8 May 2025 under the title ‘Whither Europe?’. Former Prime Minister Geir H. Haarde delivered the opening remarks. He said that he found it fascinating that in Gissurarson’s book Snorri Sturluson and Nikolaj F. S. Grundtvig, two personalities that the Icelanders well knew and respected, were described as contributors to the classical liberal tradition. He added that he and Gissurarson had began their political activities more than fifty-five years ago in the Independence Party, and that Gissurarson’s ideas had made a great impact in Iceland.

The Icelandic Research Centre for Social and Economic Affairs, RSE, and the Institute of Studies in Administration and Politics at the University of Iceland jointly held an international conference in Reykjavik on Professor Gissurarson’s book on 8 May 2025 under the title ‘Whither Europe?’. Former Prime Minister Geir H. Haarde delivered the opening remarks. He said that he found it fascinating that in Gissurarson’s book Snorri Sturluson and Nikolaj F. S. Grundtvig, two personalities that the Icelanders well knew and respected, were described as contributors to the classical liberal tradition. He added that he and Gissurarson had began their political activities more than fifty-five years ago in the Independence Party, and that Gissurarson’s ideas had made a great impact in Iceland.

Danish historian Dr. David Gress gave a talk about the nation state. The author of several books on the subject, he pointed out that in the nineteenth century in Europe nationalism and classical liberalism went hand in hand in most countries. The desire for a nation state was also a desire for devolution. The elites and the masses were united in the fight for national self-determination. This changed in the twentieth century where at least a large part of the elites turned against Western civilisation and their own countries under the influence of Marxism and other left-wing ideologies. At present, Gress submitted, there was a tension between the masses and the elites, safely ensconced in their offices in Brussels and the big capitals of Europe as well as in the media and universities. This tension was not least about immigration. The European peoples simply refuse to accept that their countries should be taken over by Muslim immigrants, bent on imposing their cultural values upon the rest of society.

Danish historian Dr. David Gress gave a talk about the nation state. The author of several books on the subject, he pointed out that in the nineteenth century in Europe nationalism and classical liberalism went hand in hand in most countries. The desire for a nation state was also a desire for devolution. The elites and the masses were united in the fight for national self-determination. This changed in the twentieth century where at least a large part of the elites turned against Western civilisation and their own countries under the influence of Marxism and other left-wing ideologies. At present, Gress submitted, there was a tension between the masses and the elites, safely ensconced in their offices in Brussels and the big capitals of Europe as well as in the media and universities. This tension was not least about immigration. The European peoples simply refuse to accept that their countries should be taken over by Muslim immigrants, bent on imposing their cultural values upon the rest of society.

Dr. Alberto Mingardi, Director of the Bruno Leoni Institute in Milan, Professor of Political theory at the IULM University, Adjunct Scholar at the Cato Institute in Washington DC and Secretary of the Mont Pelerin Society, discussed Luigi Einaudi and his theories. Einaudi was President of Italy in 1948–1955 and one of the fathers of the ‘Italian miracle’ in which rapid economic growth followed liberalisation and stabilisation after the Second World War. Mingardi pointed out that in Gissurarson’s book a distinction was made between economic integration which was desirable, and political integration which was simply a euphemism for centralisation. He argued that Einaudi would have found much to applaud in the European Union, especially the common market and increased competition, but also much to criticise, especially the tendency towards centralisation. The task was to reduce political power, not to transfer it from national capitals to Brussels. Mingardi has written a review of Gissurarson’s book in Italian, and in Icelandic two reviews of it have been published, by former Education Minister Bjorn Bjarnason and former Finance Minister Benedikt Johannesson.

Dr. Alberto Mingardi, Director of the Bruno Leoni Institute in Milan, Professor of Political theory at the IULM University, Adjunct Scholar at the Cato Institute in Washington DC and Secretary of the Mont Pelerin Society, discussed Luigi Einaudi and his theories. Einaudi was President of Italy in 1948–1955 and one of the fathers of the ‘Italian miracle’ in which rapid economic growth followed liberalisation and stabilisation after the Second World War. Mingardi pointed out that in Gissurarson’s book a distinction was made between economic integration which was desirable, and political integration which was simply a euphemism for centralisation. He argued that Einaudi would have found much to applaud in the European Union, especially the common market and increased competition, but also much to criticise, especially the tendency towards centralisation. The task was to reduce political power, not to transfer it from national capitals to Brussels. Mingardi has written a review of Gissurarson’s book in Italian, and in Icelandic two reviews of it have been published, by former Education Minister Bjorn Bjarnason and former Finance Minister Benedikt Johannesson.

Lord Borwick, of the House of Lords, explained Brexit, the decision of British voters in a 2016 referendum to leave the European Union. He said that his fellow Conservative, Prime Minister David Cameron, had been convinced that the Remainers would win the referendum. Cameron’s intention with the referendum had therefore been to remove a contentious issue from British politics once and for all. He, and the whole political establishment, was however unprepared for the result. In Borwick’s opinion those, like him, who wanted to leave mainly sought to regain British control over British affairs. Where they were wrong was in imagining that the fight was over with the victory in the referendum. The EU itself had tried to make Brexit as difficult as possible, while the political establishment had not given up trying to rejoin the EU. Borwick pointed out that there had indeed been another Brexit in 1776, British people disassociating from an Empire across the sea. This was when the Americans declared independence from the Empire based in London. They wanted to take control of their own affairs instead of obeying orders from London.

Lord Borwick, of the House of Lords, explained Brexit, the decision of British voters in a 2016 referendum to leave the European Union. He said that his fellow Conservative, Prime Minister David Cameron, had been convinced that the Remainers would win the referendum. Cameron’s intention with the referendum had therefore been to remove a contentious issue from British politics once and for all. He, and the whole political establishment, was however unprepared for the result. In Borwick’s opinion those, like him, who wanted to leave mainly sought to regain British control over British affairs. Where they were wrong was in imagining that the fight was over with the victory in the referendum. The EU itself had tried to make Brexit as difficult as possible, while the political establishment had not given up trying to rejoin the EU. Borwick pointed out that there had indeed been another Brexit in 1776, British people disassociating from an Empire across the sea. This was when the Americans declared independence from the Empire based in London. They wanted to take control of their own affairs instead of obeying orders from London.

Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson, former Prime Minister and at present Leader of the Centre Party, delivered a few closing remarks. He said that he agreed mostly with the speakers, but perhaps not entirely with Mingardi’s enthusiasm with federalism. Now was the time to defend the European nation state. He would himself fight all possible proposals for Iceland to join the European Union. Dilja Mist Einarsdottir, Member of Parliament for the Independence Party, chaired the meeting. At the end of the conference, two leaders of conservative Nordic youth, Julius Viggo Olafsson, Chairman of Young Independents in Reykjavik, and Haakon Teig from the Norwegian Conservative Students Association commented on the conference from the point of view of a new generation. They said that there seemed to be a conservative and libertarian revival among the new generation, not least in opposition to wokeism and cancel culture. Young people were once again interested in their natural heritage, including Christianity, classical architecture and naturalistic painting.

Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson, former Prime Minister and at present Leader of the Centre Party, delivered a few closing remarks. He said that he agreed mostly with the speakers, but perhaps not entirely with Mingardi’s enthusiasm with federalism. Now was the time to defend the European nation state. He would himself fight all possible proposals for Iceland to join the European Union. Dilja Mist Einarsdottir, Member of Parliament for the Independence Party, chaired the meeting. At the end of the conference, two leaders of conservative Nordic youth, Julius Viggo Olafsson, Chairman of Young Independents in Reykjavik, and Haakon Teig from the Norwegian Conservative Students Association commented on the conference from the point of view of a new generation. They said that there seemed to be a conservative and libertarian revival among the new generation, not least in opposition to wokeism and cancel culture. Young people were once again interested in their natural heritage, including Christianity, classical architecture and naturalistic painting.

The conference was well-attended, and in a reception following it, Professor Hannes H. Gissurarson gave a toast to Friedrich A. von Hayek, whose birthday it was: He was born on 8 May 1899. Gissurarson and his friends, some of whom attended the conference (Fridrik Fridriksson, Skafti Hardarson, and Audun Svavar Sigurdsson), had indeed founded the Libertarian Alliance on Hayek’s 80th birthday in 1979. Gissurarson said that the most fascinating and attractive feature of Hayek’s teachings was his incontestable recognition of inevitable individual ignorance combined with the possibility of overcoming this ignorance, both in time by traditions as accumulated knowledge and in space by transmission of knowledge through the price mechanism of the free market.

In the evening, after the conference, RSE invited the programme participants and people who had assisted with organising the conference to dinner at the renowned Reykjavik restaurant Tides where they drank red wine from Luigi Einaudi’s vineyard with Icelandic lamb and skyr: products of the North and South of Europe. From left: Gudlaugur Thor Thordarson, former Foreign Minister, Breki Atlason, Students for Liberty Europe, Alberto Mingardi, Ragnar Arnason, Chairman of the RSE Research Council, Hannes H. Gissurarson, David Gress, Haakon Teig, Lukas Schweiger, RSE coordinator, Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson and Lord Borwick.