RNH Academic Director, Professor Hannes H. Gissurarson, attended the annual Margaret Thatcher dinner organised by Brussels think tank New Direction on 22 September 2022. This time, the venue was the House of the Blackheads (medieval merchants) in Tallinn, Estonia, and the speaker of the evening was Ukrainian member of parliament Oleksiy Goncherneko, who is active in the defence of human rights at the Council of Europe. He eloquently expressed his conviction that Ukraine would repel the attack by the Russian forces under Putin.

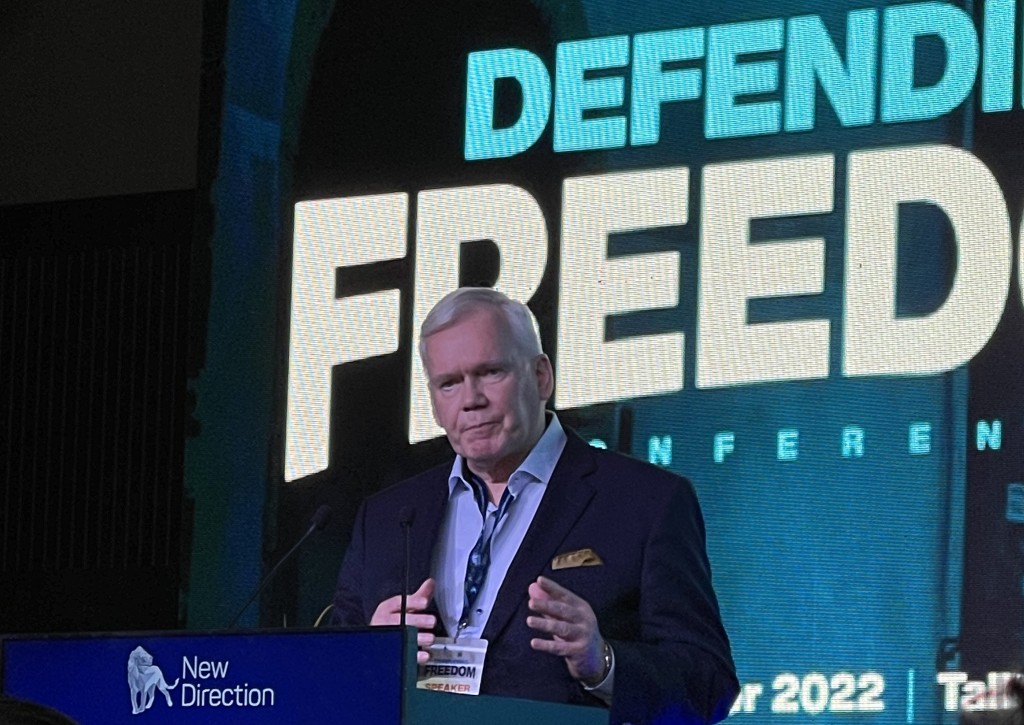

The day after the dinner, New Direction held a debate on the direction in which European centre-right parties should go in the future. Gissurarson argued for the conservative liberalism which he described in his recent book on Twenty-Four Conservative-Liberal Thinkers. Its four main pillars are private property, free trade, limited government and respect for traditions, in particular traditions developed in spontaneous voluntary associations such as families, congregations, cooperatives, sports clubs and local communities. Conservative-liberal thinkers include, Gissurarson submitted, St. Thomas Aquinas, David Hume, Adam Smith, Edmund Burke, Benjamin Constant, Alexis de Tocqueville, Ludwig von Mises, Friedrich von Hayek, Wilhelm Röpke, Michael Oakeshott, and Karl Popper.

Gissurarson said that in his opinion Hayek was perhaps the greatest representative of the conservative-liberal political tradition. Hayek’s question was how we, in spite of our inevitable individual ignorance, have been able to develop Western civilisation with its enormous variety, diversity, creativity, entrepreneurship and opportunities. His answer was that in a free society knowledge could be acquired and transmitted, between different generations through tradition and between people in different places through the price mechanism. Unlike utilitarian liberals, conservative liberals did not ignore the many ties, attachments and commitments which individuals acquire as a result of their membership in various communities.

Gissurarson made a distinction between good and bad nationalism. Good nationalism was the collective will of a community to live together, almost always based on a long, shared history and sometimes on a common language. But the community should not be closed; it had to be the subject of choice; the nation should be a daily plebiscite, in Ernest Renan’s apt phrase—a home, neither a prison nor a fortress. Bad nationalism was however aggressively directed against other communities, seeking to subdue, oppress and humiliate them. Gissurarson suggested that the War in Ukraine was between these two kinds of nationalism: the Ukrainians’ will to maintain a sovereign state which would preserve and develop their common identity, and the determination of a small clique in the Moscow Kremlin to conquer the fertile fields of Ukraine and to be seen to triumph on the international arena.

Gissurarson also made a distinction between positive and negative populism. Positive populism consisted in taking the voters seriously, but trying to direct their emotions, interests, and frustrations into socially and politically useful channels. One example was when Margaret Thatcher sold off council houses, changing by one stroke tenants into responsible house owners and her potential supporters. Negative populism was however when unscrupulous politicians try to unite the masses against some imaginary enemies, such as the rich or the Jews. It was important, Gissurarson said, to extend the moral vision to the whole of mankind, to apply the old Catholic concept of ‘universitas hominum’, but without neglecting our duties to those standing closer to us.

The other participants in the debate were Federico Ottavio Reho, Strategic Coordinator and Senior Research Officer at the Wilfried Martens Centre for European Studies, who defended christian democracy, Anna Wellisz, VP for External Affairs of the Edmund Burke Foundation, who advocated national conservatism, and John O’Sullivan, President of Danube Institute and former speechwriter for Margaret Thatcher, who stood up for traditional conservatism.