Professor Hannes H. Gissurarson, RNH Academic Director, attends the annual meeting of the European Platform of Memory and Conscience in Wroclaw, Poland, 17–19 November 2015. At the meeting he gives a presentation on a joint project of RNH and AECR, Alliance of European Conservatives and Reformists, on “Europe of the Victims” and describes a new series of anti-totalitarian writings online which RNH is publishing in cooperation with the Public Book Club (Almenna bokafelagid). The works in the series originally came out in the intellectual battle of Icelandic democrats against admirers of the totalitarian states. They will be made available online (both in Google Books and on Kindle) and also printed in limited quantities. They are targeted to students writing papers in schools and to people with general interest in history, not least in the Cold War, when democracy was embattled. The project of creating an online library of libertarian and anti-totalitarian literature is also support by the Atlas Network.

Professor Hannes H. Gissurarson, RNH Academic Director, attends the annual meeting of the European Platform of Memory and Conscience in Wroclaw, Poland, 17–19 November 2015. At the meeting he gives a presentation on a joint project of RNH and AECR, Alliance of European Conservatives and Reformists, on “Europe of the Victims” and describes a new series of anti-totalitarian writings online which RNH is publishing in cooperation with the Public Book Club (Almenna bokafelagid). The works in the series originally came out in the intellectual battle of Icelandic democrats against admirers of the totalitarian states. They will be made available online (both in Google Books and on Kindle) and also printed in limited quantities. They are targeted to students writing papers in schools and to people with general interest in history, not least in the Cold War, when democracy was embattled. The project of creating an online library of libertarian and anti-totalitarian literature is also support by the Atlas Network.

The first book in the series came out 17 June 2015, when the Public Book Club celebrated its 60th anniversary. It was Articles on Communism (Greinar um kommunisma) by the famous British philosopher Bertrand Russell, also a Nobel Laureate in literature. These articles appeared in Icelandic newspapers and magazines in 1937–1956. Professor Gissurarson writes a Foreword and some Notes.

The first book in the series came out 17 June 2015, when the Public Book Club celebrated its 60th anniversary. It was Articles on Communism (Greinar um kommunisma) by the famous British philosopher Bertrand Russell, also a Nobel Laureate in literature. These articles appeared in Icelandic newspapers and magazines in 1937–1956. Professor Gissurarson writes a Foreword and some Notes.

The second book in the series came out 19 June 2015, when a century had passed since Icelandic women acquired the right to vote in parliamentary elections. It was Women in Stalin’s Prison Camps (Konur i thraelakistum Stalins), the memories of two women who were without any guilt whatsoever kept in Soviet prison camps. Extracts of these memories appeared in Icelandic newspapers in 1951, 1953 and 1975. The authors were Elinor Lipper from Switzerland and Aino Kuusinen from Finland. Professor Gissurarson writes a Foreword and some Notes.

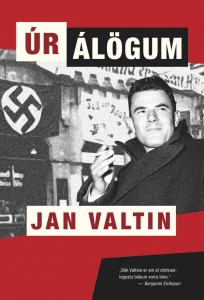

The third book in the series came out 23 August, which had been designated by the European Parliament as a Remembrance Day of the Victims of Totalitarianism. It was Out of the Night (Ur alogum) by Jan Valtin, a pseudonyn for Richard Krebs, who had been a Gestapo spy, but in reality a Comintern counter-intelligence agent. In 1941, this racy and readable autobiography was a best-seller in the United States. When the Social Democratic Book Club published the first part of it in the summer of 1941, the Icelandic communists organised a campaign against it with the result that the second part was only published in 1944, by “A handful of comrades”. The well-knwon communist writer Halldor K. Laxness and a communist renegade, economist Benjamin H. J. Eiriksson, debated the book and its message. Professor Gissurarson writes a Foreword and some Notes.

The third book in the series came out 23 August, which had been designated by the European Parliament as a Remembrance Day of the Victims of Totalitarianism. It was Out of the Night (Ur alogum) by Jan Valtin, a pseudonyn for Richard Krebs, who had been a Gestapo spy, but in reality a Comintern counter-intelligence agent. In 1941, this racy and readable autobiography was a best-seller in the United States. When the Social Democratic Book Club published the first part of it in the summer of 1941, the Icelandic communists organised a campaign against it with the result that the second part was only published in 1944, by “A handful of comrades”. The well-knwon communist writer Halldor K. Laxness and a communist renegade, economist Benjamin H. J. Eiriksson, debated the book and its message. Professor Gissurarson writes a Foreword and some Notes.

Professor Hannes H. Gissurarson is the general editor of the series. Sigurgeir Orri Sigurgeirsson designs the book covers; Kristinn Ingi Jonsson is in charge of proof-reading; Fridbjorn Orri Ketilsson scans the books; and Hafsteinn Arnason oversees the technical aspects of publication online. What is also stressed in the publication of the series is the important contribution by Icelanders who took up the fight against the totalitarians, Larus Johannesson, Geir Hallgrimsson, Eyjolfur K. Jonsson and others.

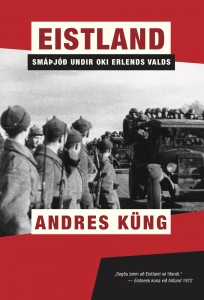

In 2016, the online publication of five works are planned: 1) Khruschev’s Secret Speech on Stalin, 25 February, sixty years after its delivery, which was a major blow for Icelandic communists; 2) El campesino: Life and Death in the Soviet Union by Valentín Gonzalez and Julián Gorkin, 17 July, when eighty years have passed since the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, in which El campesino fought, before fleeing to the Soviet Union; 3–4) Baltic Eclipse by Ants Oras and Estonia — A Small Nation under the Yoke of Foreign Power by Anders Küng, 26 August, when 25 years have passed since Iceland became the first country to re-recognise the independence of the Baltic countries. David Oddsson, Prime Minister in 1991, had translated Küng’s book in 1973, then a student of law; 5) Service, Servitude, Escape by Aatami Kuortti, a 1934 account by an inmate of the Gulag, 25 December, when 25 years have passed since the collapse of the Soviet Union. In some cases, events will be organised in connection with the publication of the books.

In 2016, the online publication of five works are planned: 1) Khruschev’s Secret Speech on Stalin, 25 February, sixty years after its delivery, which was a major blow for Icelandic communists; 2) El campesino: Life and Death in the Soviet Union by Valentín Gonzalez and Julián Gorkin, 17 July, when eighty years have passed since the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, in which El campesino fought, before fleeing to the Soviet Union; 3–4) Baltic Eclipse by Ants Oras and Estonia — A Small Nation under the Yoke of Foreign Power by Anders Küng, 26 August, when 25 years have passed since Iceland became the first country to re-recognise the independence of the Baltic countries. David Oddsson, Prime Minister in 1991, had translated Küng’s book in 1973, then a student of law; 5) Service, Servitude, Escape by Aatami Kuortti, a 1934 account by an inmate of the Gulag, 25 December, when 25 years have passed since the collapse of the Soviet Union. In some cases, events will be organised in connection with the publication of the books.

Future republications include the Icelandic translation of the Black Book of Communism, edited by Stéphane Courtois, a collection of articles about Communist China by Johann Hannesson, who worked as a missionary in China, a collection of speeches against communism by leading Icelandic intellectuals, poet Tomas Gudmundsson and writers Gunnar Gunnarsson, Gudmundur G. Hagalin, Kristmann Gudmundsson and others, Darkness at Noon and Soviet Myth and Reality by Arthur Koestler, Nineteen Eighty Four by George Orwell, I chose Freedom by Victor Kravchenko and The God That Failed by Koestler, André Gide and others.

US investor and writer Bill Browder gives a talk in the Festivities Hall of the University of Iceland Friday 20 November 2015 at 12–13, sponsored by RNH, the Public Book Club (Almenna bokafelagid) and the Institute of International Affairs at the University of Iceland. The title of the talk is “Putin’s Russia”. In Red Notice, a book recently published in Icelandic, Browder describes his eventful life and the reckoning with Putin. The grandson of Earl Browder, leader of the US Communist Party, Bill Browder rebelled against the left-wing views of his family and studied finance at Stanford University. He became one of the most successful investors in Russia after the collapse of communism, in a very unstable environment. For a while he supported Putin against the Oligarchs, but then Putin turned against him. When Browder’s Russian friend and lawyer, Sergey Magnitsky, was imprisoned by the Russian authorities, tortured and left to die, Browder took a vow that justice should be obtained for him. On his recommendation, the US Congress passed the “Magnitsky Act”, barring those responsible for Magnitsky’s death from entering the United States or doing any business on US territory. Allegedly, Putin regards Browder as his Enemy No. One. Browder’s book is being published in 22 languages. Its name is derived from a “red notice” which Interpol, at the insistence of Russian authorities, put out against Browder for alleged crimes in Russia, withdrawing it almost immediately when the charges were found to be groundless. Browder’s talk, as well as the publication of his book, forms a part of the joint project of RNH and AECR, the Alliance of European Conservatives and Reformists, on “Europe, Iceland and the Future of Capitalism”.

US investor and writer Bill Browder gives a talk in the Festivities Hall of the University of Iceland Friday 20 November 2015 at 12–13, sponsored by RNH, the Public Book Club (Almenna bokafelagid) and the Institute of International Affairs at the University of Iceland. The title of the talk is “Putin’s Russia”. In Red Notice, a book recently published in Icelandic, Browder describes his eventful life and the reckoning with Putin. The grandson of Earl Browder, leader of the US Communist Party, Bill Browder rebelled against the left-wing views of his family and studied finance at Stanford University. He became one of the most successful investors in Russia after the collapse of communism, in a very unstable environment. For a while he supported Putin against the Oligarchs, but then Putin turned against him. When Browder’s Russian friend and lawyer, Sergey Magnitsky, was imprisoned by the Russian authorities, tortured and left to die, Browder took a vow that justice should be obtained for him. On his recommendation, the US Congress passed the “Magnitsky Act”, barring those responsible for Magnitsky’s death from entering the United States or doing any business on US territory. Allegedly, Putin regards Browder as his Enemy No. One. Browder’s book is being published in 22 languages. Its name is derived from a “red notice” which Interpol, at the insistence of Russian authorities, put out against Browder for alleged crimes in Russia, withdrawing it almost immediately when the charges were found to be groundless. Browder’s talk, as well as the publication of his book, forms a part of the joint project of RNH and AECR, the Alliance of European Conservatives and Reformists, on “Europe, Iceland and the Future of Capitalism”.